Disease in Bram Stoker's Dracula

Tatiana continues to examine the correlation between disease and vampirism, this time within literature, as she delves into Dracula, Bram Stoker’s 1897 defining work of Gothic horror.

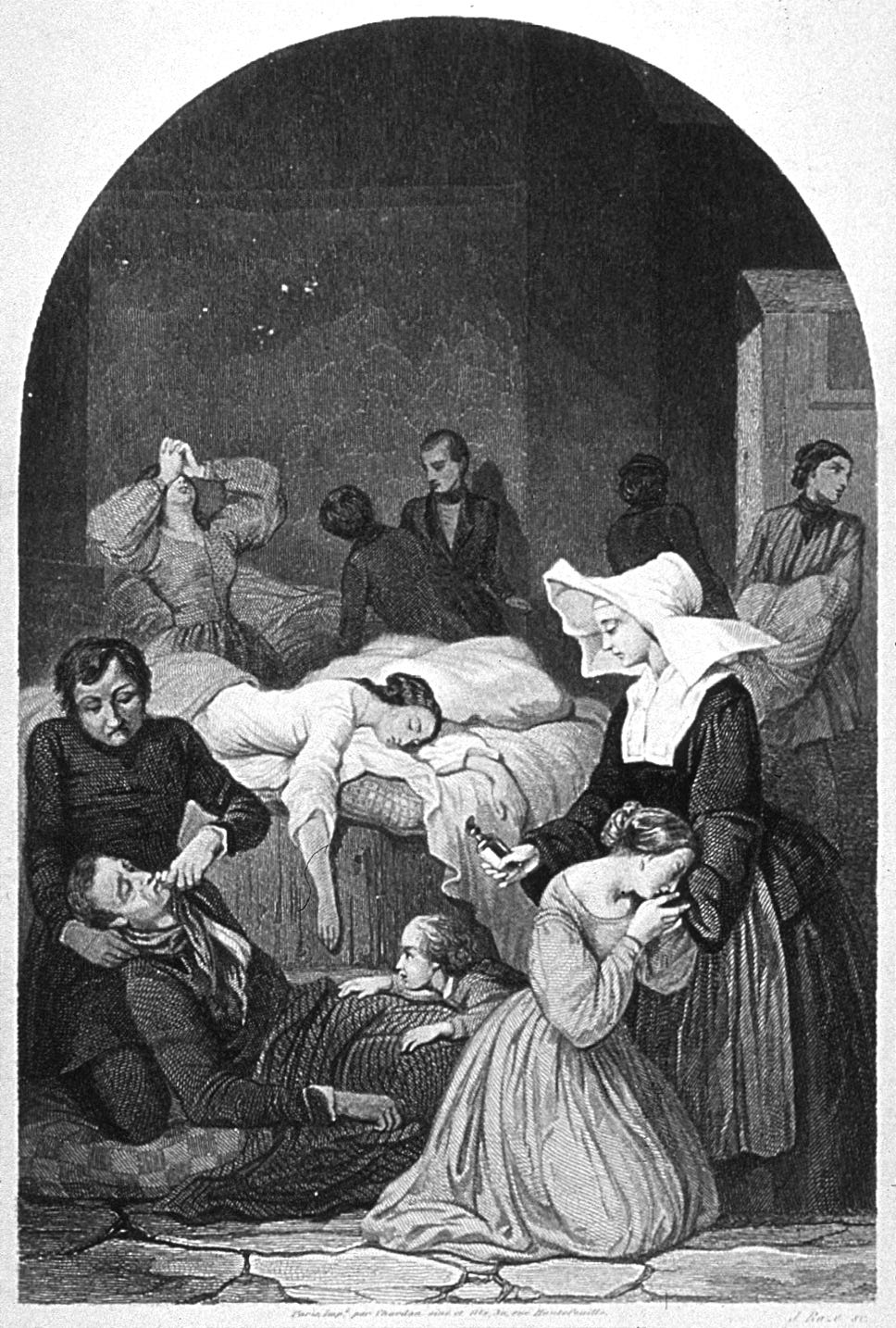

“By twos and threes our dead neighbors were carried away. One morning, four were carried at once dead out of the opposite house.” Charlotte was fourteen years old when Sligo became the most infected town in Ireland during the cholera outbreak of the early 1830s. The mortality rate was nearly 50%, killing around 2000 people in Sligo alone. The sick died within three hours of infection; most inhabitants ended up fleeing. The hospital grounds were strewn with corpses and there was no one to bury them. Mass graves were dug in haste. There were cases of people on the brink of death being buried alive. “In a very few days the town became like a city of the dead.” Charlotte and her family were spared, but the experience was deeply traumatic. Forty years later, she wrote a detailed account of the horrific events in her memoir, Experiences of the Cholera in Ireland. By then, Charlotte had become Mrs. Stoker, had moved to Dublin, and had brought up a large family, including two prominent sons: Thornley and Bram. The first a distinguished surgeon and president of the Irish Royal Academy; the second the acclaimed author of Dracula.

The two boys naturally developed an interest in medicine growing up with their mother’s plague stories and an uncle, William Stoker, who was an esteemed physician involved with the Dublin Fever Hospital, an organization specialized in infectious disease. Throughout the 19th century, malady was ever present in the minds of the British, who suffered murderous waves of cholera and tuberculosis, living in constant fear of a pandemic spreading from the continent unto their isles1. Unfortunately, Victorian physicians mostly rejected the idea that disease could be transmitted through contagion. Miasmatism was the consensus, attesting that diseases like cholera were caused by “bad air”, fumes of rotting organic matter, poor hygiene, foul smells, fogs, dust, and stagnant waters. Only near the end of the century, not long before Bram Stoker started working on Dracula, did the medical field begin to understand infection, thanks to the groundbreaking research of John Snow, Louis Pasteur, and Robert Koch. Germ theory then rapidly replaced obsolete miasmatism: bacteria were the culprits and (like vampires) only survived by preying on people. Invisible wandering specks were infiltrating human bodies, and eventually killing them ––a strange and nightmarish discovery2. “The air was full of specks, floating and circling in the draught from the window. Quicker and quicker danced the dust; the moonbeams seemed to quiver as they went by me into the mass of gloom beyond. More and more they gathered till they seemed to take dim phantom shapes.”

Bram Stoker found vast inspiration to fuel his tale of vampirism in the various beliefs abounding during his time. Stoker’s great tour de force was managing to tie them all into his central character, the eccentric Doctor Van Helsing, who represents every medical theory at once combined with a deep deference for the invisible, the impossible. In that sense, Van Helsing is the ideal scientist, never ruling out any hypothesis, yet offering pragmatic solutions while taking into account the potential massive scale of spiritual consequences. “But to fail here, is not mere life or death. It is that we become as him; that we henceforward become foul things of the night like him—without heart or conscience, preying on the bodies and the souls of those we love best.” Van Helsing proclaims that their heroic stand against vampiric infection is a crusade, a holy war between good and evil, light and darkness: they are fighting for their souls and the future of mankind. Here, Stoker is voicing the fears found in so many accounts of physicians during the cholera outbreak –– it felt like end times, they were fighting a losing battle in an atmosphere of frenzied, desperate, and apocalyptic horror. And when the contagious nature of these epidemics was finally revealed, many people with survivor guilt were wondering in retrospect if they had the blood of their loved ones on their hands. It was a traumatized society that Stoker’s readers were born into, most had probably lost several family members to disease, and all had undoubtably heard gruesome firsthand tales.

Unclean, unclean! I must touch him or kiss him no more. Oh, that it is I who am now his worst enemy! During the 19th century, disease was often conflated with poverty, promiscuity, and villainy. Much commoner than cholera and tuberculosis, syphilis flourished in the cities of Victorian England, and the risk of sexually transmitted ills was a constant threat for the poor, the prostitutes, and the upper-class gentlemen who frequented them. “Elegant” illnesses like consumption were dignified enough for the aristocracy, but the so-called venereal plague was considered shameful and dirty.3 In Dracula, vampiric infection is akin to a sexual act where blood replaces semen –– the disease is transmitted through penetration (of fangs) and exchange of bodily fluids in a passionate encounter that is unmistakably erotic and depraved. As a consequence, the women who fall under Dracula’s spell and become infected are debased. From demure virgins they become syphilitic whores. The sweetness was turned to adamantine, heartless cruelty, and the purity to voluptuous wantonness.

Both of Dracula’s preys, Lucy and Mina, are best friends since childhood though everything opposes them: Lucy is wealthy, spirited, uninhibited, full of coquettish charm –– she represents the decaying world of aristocracy; Mina is middle-class, conservative, hard-working, down-to-earth, and interested in science and progress –– she is the epitome of the model Victorian woman. While both get infected by the vampire through attacks that are intrinsically sexual, Lucy is portrayed as a subconsciously willing victim whereas Mina’s encounter with the vampire is depicted as a violent rape. With his left hand he held both Mrs. Harker’s hands, keeping them away with her arms at full tension; his right hand gripped her by the back of the neck, forcing her face down on his bosom. Although Mina is filled with despair and self-loathing at feeling unclean after she is infected, to the group of men battling the ills of an ante-scientific world, she symbolizes the good that is worth fighting and dying for. She represents the light emerging from the darkness, the future liberated from the past.

Throughout most of Stoker’s life, the threat of cholera, tuberculosis, rabies, and syphilis epidemics perpetually hung over Europe, and the bubonic plague was still very much alive in everyone’s common memory. Victorian cities could swiftly turn into death traps. Bram Stoker used the metaphor of the vampire and the framing of the Gothic novel to embody an era of widespread nosophobia –– the fear of falling ill –– while a suspicious population lived in terror, and doctors scrambled to find causes and cures to nightmarish pandemics. Today, the memory of Covid-19 is still fresh in our minds. Strangely, there has still been no recap, no stock taken, no record set straight, no mea culpas of any kind. Sure, it wasn’t the black plague or consumption, it wasn’t even close, but it was nothing like anyone alive had ever experienced, and we were not prepared for it. We –– and our governments –– now want to pretend it never happened, but I don’t care if people try to convince me that everything is back to normal, I know it’s not true. I know we were collectively traumatized and that we’re still trying to understand what the hell happened. Many of us have since developed forms of illness anxiety disorders which are sometimes difficult to contain. A new set of pandemic induced habits are still burnt in our brains. A few of us still wear masks alone in our cars. Without even being aware of it, we tread carefully, we watch who is sneezing, who is disinfecting their hands. We have learned how to be suspicious of each other and always wonder whether a nosferatu walks among us.

Like most pandemics in British history –– including the 1832 cholera outbreak –– it is a ship that brings Dracula to Britain.

Similarly to infectious disease, vampires cannot enter your house if you don’t invite them in. You are “safe” as long as you stay “quarantined”.

Bram Stoker himself succumbed to syphilis in 1912.